Joseph Brodsky on Yevgeny Rein and his “almost infantlike thirst for words”

Wednesday, December 29th, 2021

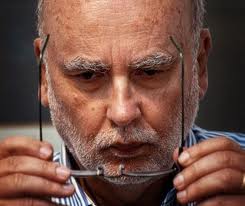

Today is the 86th birthday of Yevgeny Rein, one of Russia’s leading poets and winner of the prestigious Pushkin Prize. Fortunately, Los Angeles Review of Books editor Boris Dralyuk reminded me of the occasion on Twitter. What better way to celebrate than cite the comments of his friend, the Nobel poet Joseph Brodsky?

Both were in the quartet of “Akhmatova’s orphans,” the group of young poets who were protégés of Anna Akhmatova in the years before her death in 1966. The quartet also included Dmitri Bobyshev and Anatoly Naiman.

Brodsky called Rein “metrically the most gifted Russian poet of the second half of the 20th century.” He continues in a 1994 Commentary introduction:

“… the death of the world order for Rein is not a singular event but a gradual process. Rein is a poet of erosion, of disintegration—of human relationships, moral categories, historical connections, and dependencies of any nature binomial or multipolar. And his verse, like a spinning black record, is the only form of mutation accessible to him, a fact testified to above all by his assonant rhymes. To top it all, this poet is extraordinarily concrete, substantive. Eighty percent of a Rein poem commonly consists of nouns and proper names. The remaining 20 percent is verbs, adverbs, and, least, adjectives. As a result, the reader often has the impression that the subject of the elegy is language itself, parts of speech illuminated by the sunset of the past tense, which casts its long shadow into the present and even touches the future.

“But what might seem to the reader a conscious artifice, or at the very least a product of retrospection, is not. For the surplus materiality, the oversaturation with nouns, was present in Rein’s poetry from the beginning. In his earliest poems, at the end of the 1950s—in particular in his first poem, “Arthur Rimbaud”—one notes a kind of “Adamism,” a tendency to name things, to enumerate the objects of this world, an almost infantlike thirst for words. For this poet, the discovery of the world accompanied the development of diction. Ahead of him there was, if not life, then at least a huge dictionary.”

He concludes: “Russian poetry has never had enough time (or space, for that matter). This explains its intensity and wrenching quality—not to say hysteria. What has been created in the existent parameters over the last hundred years—under Damocles’ sword—is extraordinary, but too often colored by a sense of ‘now or never!'”

Well, read the whole thing here, along with Brodsky’s selection of his poems.

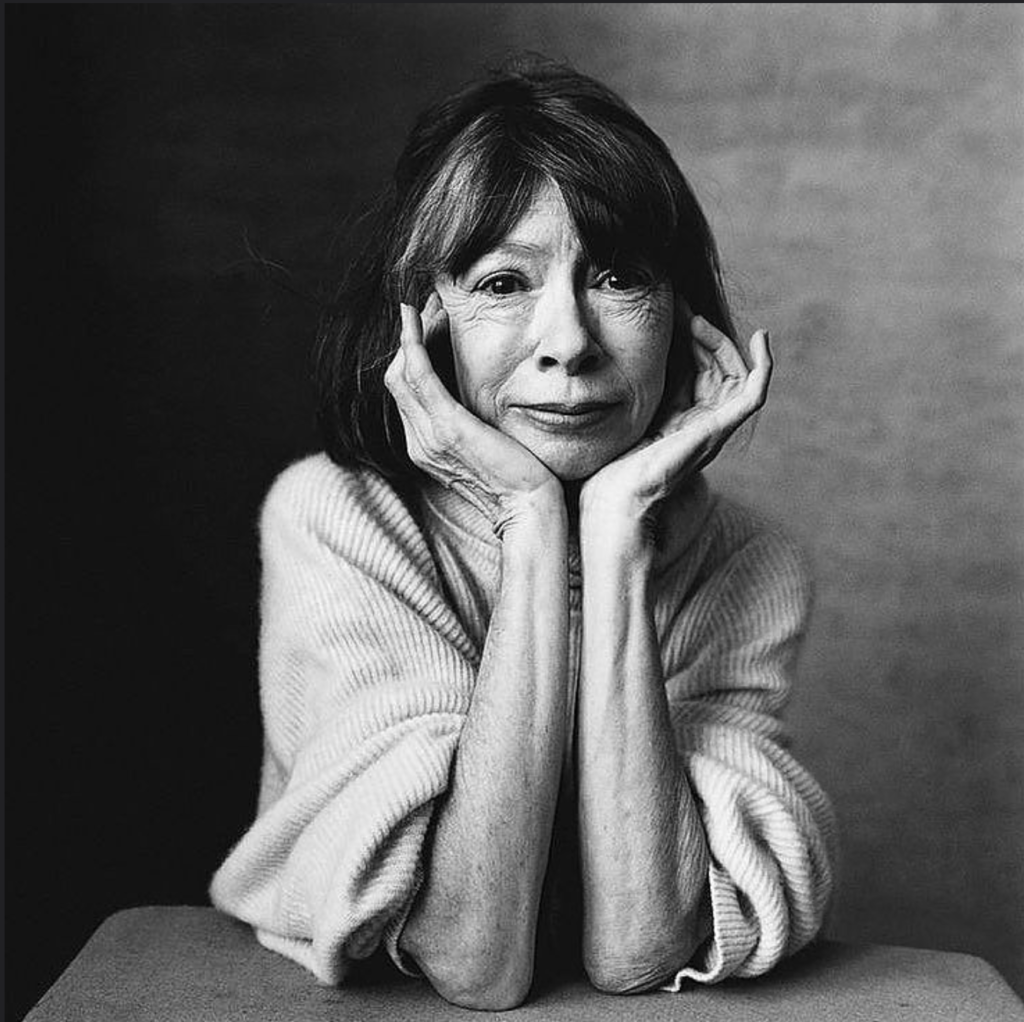

Nota bene: Photo above taken by East Bay photographer Terrence McCarthy. We worked together at the Michigan Daily long ago. The photo is reproduced in this year’s The Man Who Brought Brodsky into English: Conversations with George L. Kline. Read more about that book here.