Nothing makes “the meaning of life” less persuasive than much talk about it. The same is true of hope for the new year. “You gotta have hope. Mustn’t sit around and mope. Nothing’s half as bad as it may appear. Wait’ll next year and hope.” So sang Peggy Lee, back when I was growing up. The sentiment is familiar, almost compulsory—cheerful, reassuring, and exhausting. Hope becomes a duty, something you are supposed to have rather than something to live with.

Virginia Woolf thought about life differently. She believed it isn’t made up only of events or achievements, but of brief “moments of being” that don’t announce themselves—flashes of awareness that shimmer and vanish, yet leave a trace. A sentence that names a feeling not quite articulated before. An insight that unsettles what once seemed settled. A question that stays alive days or even weeks later. These moments don’t arrive labeled as hope, but they change how we see.

Public life increasingly runs in the opposite direction. It is shaped less by what people hope to build together than by who they are against: red versus blue, “real America” versus its enemies, every election a last stand, every defeat a betrayal. Nothing is allowed to settle. The fight must always go on, because without the fight, there is nothing left to hold.

We see this whenever leaders keep conflict alive by pointing outward—toward a villain abroad (the latest, Venezuela’s Maduro), a traitor within, or a threat just vague enough to absorb blame. The names change. The effect doesn’t.

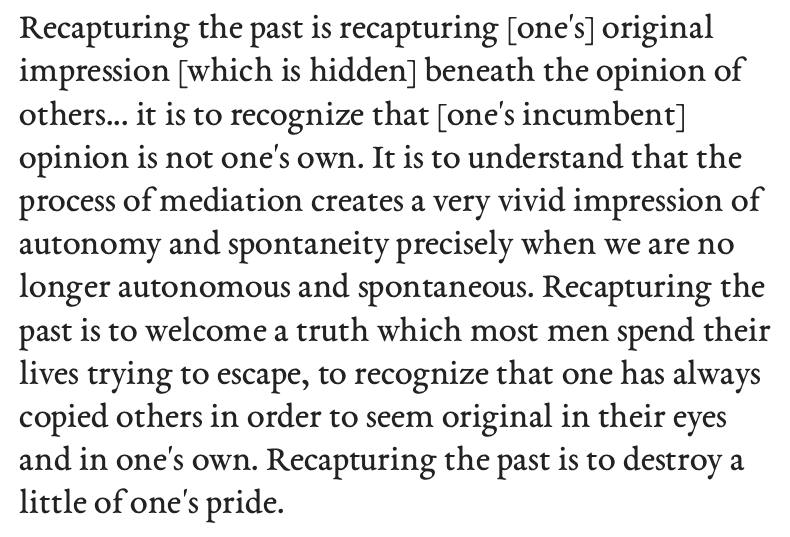

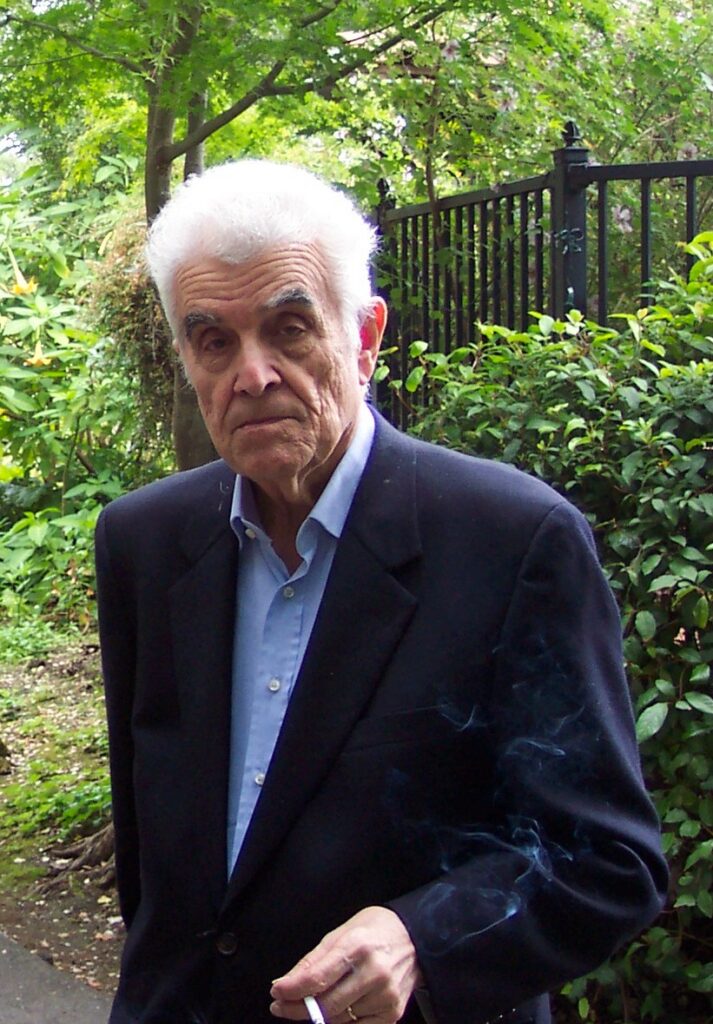

René Girard identified the pattern. When enemies are required to define who we are, common purpose becomes common hatred. Imitated desires ensure rivalry, and relief is found by assigning blame. Sometimes the target is a group—“godless liberals,” Trump supporters. Sometimes it is an abstraction that cannot answer back: the economy. In each case, a scapegoat absorbs the disorder, creating unity not through truth but through exclusion. Politics knows this rhythm well.

Friedrich Nietzsche named a similar dynamic ressentiment. Blame supplies meaning. Frustration no longer seeks remedy; it seeks an offender. “I am right” is no longer enough—it must become “you are wrong.” Morality becomes adversity. The weakness politics fears is renamed vulnerability in personal relationships—and treated as moral capital.

We see this logic at work in ordinary places: a school board meeting where every proposal sounds like an attack; a neighborhood forum that turns into a trial; an online exchange where no concession counts, only the next offense. Solving the problem matters less than naming the culprit. Even victories feel thin—each one merely reveals the next foe—until resolution itself begins to look suspect, or even a letdown. (Photo at right by Ewa Domańska)

Rivalry demands a victim, and ressentiment a target. Hostility becomes the point. Identity forms around opposition, and when one grievance fades, another takes its place. Without an enemy, the story collapses.

Earlier struggles for justice, however flawed, aimed at ends that could at least be named and settled: a law changed, a right secured, a barrier removed. Now facts, compromises, and even concessions rarely curb anger, because politics feeds on grievance rather than resolution.

The roots are as much psychological as political. Nietzsche saw how suffering that cannot be acted upon becomes someone else’s fault. Hurt hardens into judgment; disappointment turns into injustice. It can feel easier to be wronged than responsible. We imitate one another’s desires and then turn on one another when those desires collide. Small differences are exaggerated to keep opposition alive. (Photo of René Girard by Ewa Domańska)

Democracy has to offer other sources of commitment—ones that do not depend on having an enemy. People need things worth showing up for together: work worth doing, care given and received, shared projects that draw energy from devotion rather than grievance.

For us, that may begin—or begin again—modestly: staying at the table when it would be easier to walk away and feel justified. Doing the unglamorous work of keeping a school, a neighborhood, a church, a union, or a family from coming apart, even when no victory can be claimed and no one notices.

It is tempting to think moral seriousness must announce itself as a crisis. Moral life begins sooner than that. It is practiced without spectacle, sustained in situations with no spotlight and no applause: taking out the trash for an elderly neighbor, watching a friend’s kids, fixing a loose step, shoveling a driveway before work—the low hum of ordinary care.

These “moments of being” belong to no side. They offer no scapegoat, no enemy to drive out. There is nothing glamorous about them—only the steady practice of showing up.

The world does not move only through power or headlines. Sometimes it moves through memory, attention, and ordinary acts that never become slogans. The full circle isn’t flashy. It holds.

Notes and reading

- Venezuela – Maduro abducted. The familiar patterns discussed in this post apply: mimetic rivalry, ressentiment, and scapegoating.

Sunday morning: While a U.S. citizen, I grew up in Venezuela, which became my home country—alma mia. The Hugo Chávez > Nicolás Maduro regime has been brutal and corrupt. So was the right-wing dictatorship that Venezuelans themselves had overthrown in 1958, to the dismay of the U.S., which had been receiving 90% of national oil revenues from the American oil companies that effectively owned the oil fields and have since been nationalized under incompetent management.

What followed the earlier dictator’s demise was an attempt at democracy that descended into chaos: the very dynamic that had enabled authoritarianism to return under a different banner then inspired the rise of the left-wing regime just overthrown.

Apparently, the U.S. president expects to “run the country” with the (former) dictator’s loyal Vice-President, not the Nobel Peace Prize-winning opposition leader, María Machado, whose electoral victory had been denied by Maduro and called “rigged.” The U.S. itself backed the extraction of Machado in December 2025, just four weeks ago, even though she had become a vocal supporter of our own president.

— One response to Donald Trump could be, “Been there. Done that. It doesn’t work.”

Media commentary is now overwhelming. Among the strongest are Timothy Snyder, an American historian of Europe and a public intellectual in both the United States and Europe, and Joyce Vance, a former U.S. Attorney.

The figure of the scapegoat extends beyond its biblical origins in Leviticus to many religious and cultural rituals of expulsion intended to contain disorder and restore unity. Mary Douglas’s Purity and Danger and Freud’s Totem and Taboo remain classic studies of how pollution, exclusion, violence, and belonging intertwine in human communities. Earlier cultures marked the New Year by naming and containing scapegoating; we mark it by denying it—while practicing it endlessly.

Friedrich Nietzsche, On the Genealogy of Morals, trans. Walter Kaufmann and R. J. Hollingdale (1989). First Essay, §§10–11.

René Girard, Violence and the Sacred, trans. Patrick Gregory (1977), esp. chs. 2–4; and The Scapegoat, trans. Yvonne Freccero (1986).

“low-humming rhythm of simplicity”—Rituparna Sengupta, “Each Leaf a Second,” World Literature Today (January/February 2026). Sengupta researches and writes on literature, cinema, and popular culture. O. P. Jindal Global University, India.

Moral progress is annoying – Daniel Kelly and Evan Westra, Aeon (June 2024). Affective friction: the misalignment between our internalized norm psychology and new or unfamiliar social norms. Kelly and Westra are philosophers at Purdue University who work on issues in moral and cognitive science. (Compare “cognitive dissonance”)

[Virginia Woolf—The phrase “moments of being” comes from her autobiographical writings. See Woolf, Moments of Being, ed. Jeanne Schulkind (1976).]

More from the remarkable William C. Green:

Christmas, after all

Room for Love

About 2 + 2 = 5

2 + 2 = 5 is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support this work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.